Establishing behaviour change through the Theory of Planned and Expected Behaviour

The analysis of behavioural change covers a large area of study crossing multiple disciplines including social studies, economics and psychology.

Some elements of the study of behavioural change focus on interventions and their ability to drive change in behaviours through explicit testing in ‘lab’ conditions (i.e. interventional psychology and experimental economics). Others seek to understand the willingness of respondents to change behaviour (e.g. contingent behaviour/valuation analysis) in order to consider explicit policies to drive behavioural change. Still others focus on a descriptive approach characterising the elements underpinning behavioural change and seek to define those in terms of internal (psychological), social (normative), and external (environmental) factors. The latter approach is of particular interest in program evaluation and intervention design sectors as it provides an inductive basis for other, interventionist, mechanisms to be developed and assessed.

In any analysis of behaviour change, two aspects often prove to be difficult:

-

Establishing long-lasting behavioural changes is known to be highly difficult with focus participants of behavioural change programs showing substantial recidivism – a reversion to old habits, and;

-

Establishing proof of impact is both an important element for a program to generate ongoing interest for community and funding support and for a program to seek to adapt to changing circumstances, including a context that may change as the program succeeds in its mission.

How can the theory of planned behaviour help achieve longer term behaviour change?

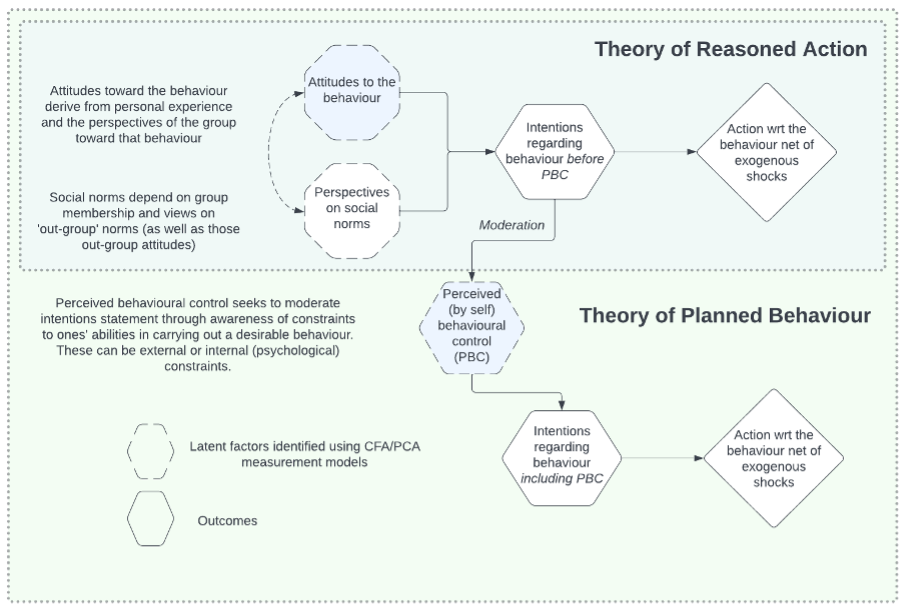

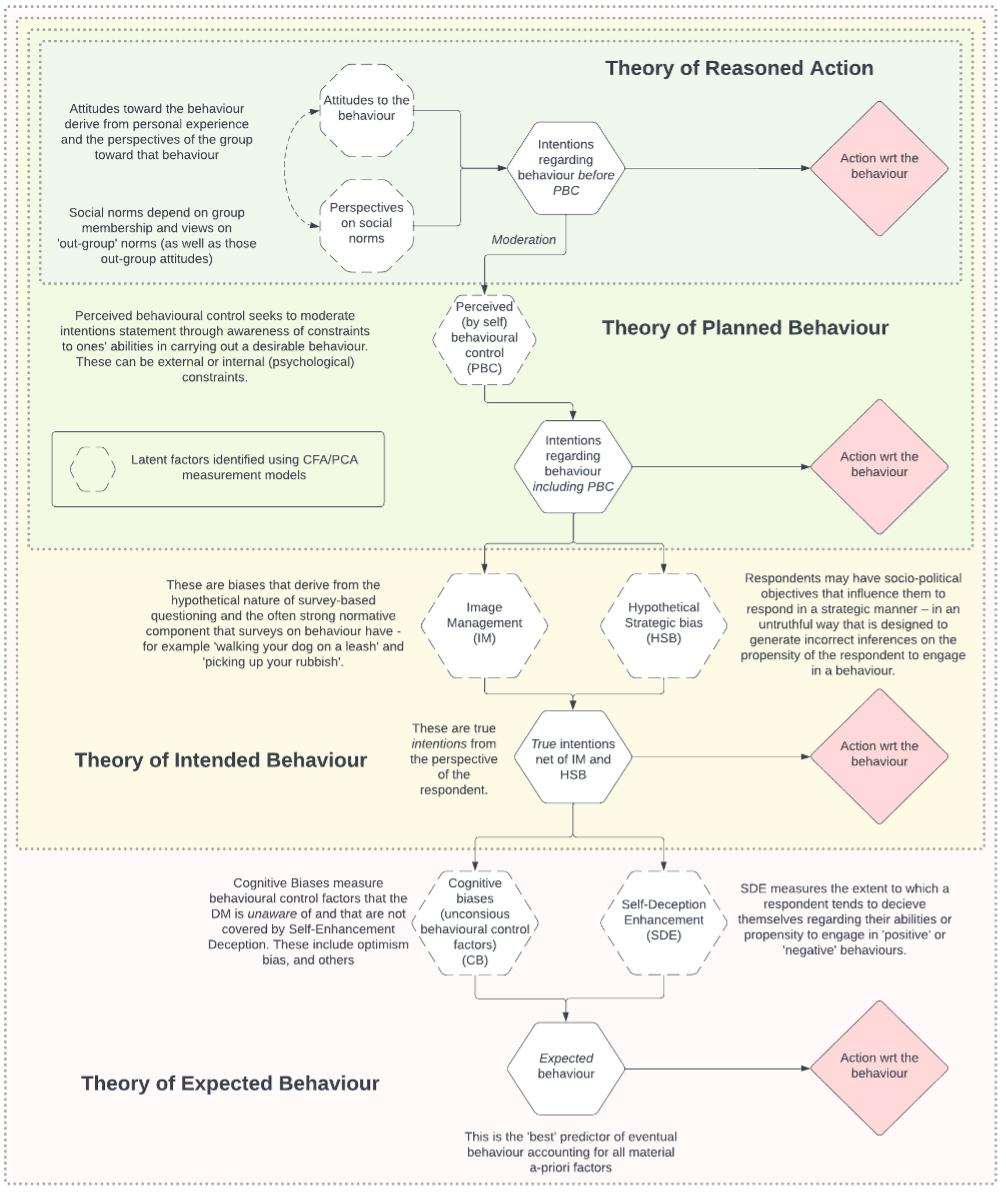

The Theory of Planned Behaviour assumes that the core driver of a final behaviour is the intention to act. The stronger the intention, the more likely that the behaviour will eventuate. The Theory of Planned Behaviour is a simple extension of the earlier Theory of Reasoned Action, which only includes attitudes toward the behaviour and perceived social norms as antecedents to intentions regarding the behaviour. The Theory of Planned Behaviour extends this theory to include the awareness of the decision maker with respect to their own ability to control their own behaviour – whether due to external factors (e.g. family constraints or kinship claims on time/finances) or due to psychological factors (e.g. knowledge that one is often not well organised or that one is often ‘late’ to appointments).

The elements in the theory of planned behaviour include:

Attitudes toward the behaviour is targeted at identifying the extent to which an individual feels that a behaviour is positive or negative with respect to their own objectives. For example, “Saving money will help me feel more/less stressed over my finances” and “saving money is important/not important for achieved financial independence”.

Social Norms seeks to understand the social context of the proposed behaviour – how the behaviour is viewed as a part of the social environment, as viewed by the respondent. For example, “my family tend to save more than I do”.

Perceived behavioural control element seeks to account for constraints or facilitators of intentions.For example, the knowledge that a person is financially constrained might limit their stated intention to ‘save more money’.

Moving towards a more complete model – the theory of expected behaviour’

Whilst the Theory of Planned Behaviour has been shown to be popular as a tool to assess the drivers of intended behaviour, it has also been shown to have limited validity in terms of predicting eventual behaviour. Much of this may be attributed to exogenous events – for example where sudden unforeseen expenses reduce actual savings from what was intended. But many critiques point to shortcomings of the Theory of Planned Behaviour in predicting actual behaviour, rather than statements on intended behaviour.

The separation between stated (fiction) and actual (fact) behaviours is, in many cases, considerable. There are a range of factors that are known to generate such differences that are summarised below:

Social desirability bias is a well-established feature of survey responses, where respondents answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favourably. This is either as an attempt to manage image to the interviewer, or an unconscious self-deception to maintain ego.

Hypothetical strategic bias refers to the consideration that people may, in some circumstances, react differently in a hypothetical, as opposed to real, decision problem. Specifically, if a respondent views responses to questions on intended behaviour as influencing policy/program operation, and that potential changes arising from that influence are material to the respondent, then they have an incentive to respond in a strategic way.

Cognitive biases have been a core element of research for over 50 years and describe the range of unconscious beliefs and approaches that lead to decision makers making choices that are suboptimal for their own goals and preferences.

Given these factors, at Heuris we have extended the Theory of Planned Behaviour to provide a more complete model of actual behaviour. This is by controlling for social desirability biases and hypothetical strategic bias to uncover true intentions of behaviour, and then control for cognitive and other biases that can reveal a best prediction of their expected behaviour. We call this the Theory of Expected Behaviour.

How we can help you

Through the Theory of Expected behaviour, Heuris can help in your analysis of analysis of behaviour change through:

-

Improved program adaptability through ongoing learning and identification of shortcomings/opportunities.

-

The description of key control points (behavioural factors) for interventions to shift behaviours of target groups and the associated types of intervention that work for those control points.

-

Improved predictions around eventual behaviour that can provide for improved forecasting of behaviours and returns to proposed programs.

-

The creation of a framework that can control selectivity biases based on pre-trial matching derived from Theory of Expected Behaviour factors and relevant socio-economic variables.

We can also assist you

- Survey co-design.

- Data collection methods, including the building of online or excel based tools and methods for data storage and maintaining anonymity.

- Data analysis, including structural equation modelling and econometric analysis.

- Reporting of data analysis using clear and approachable methods.

- The development of rapid assessment tools that can provide for the targeting of interventions based on behavioural factors.